Follow us on Facebook @FHofDW

Jacob Vile

37 & 147, Beach Street

97 Lower Street

Occupation: Watchmaker, Silversmith and Bath House Proprietor

In researching Bathing in Deal We came across Jacob Vile as the proprietor of Royal Adelaide Baths which was once situated on Beach Street opposite to where Adelaide House still stands. Soon after finishing ‘Bathing in Deal’ we came across two small pieces of paper at the Deal Museum. Both of these are receipts for work done by a Jacob Vile who, with such an unusual name must be the same man.

While Jacob seemed to live quite an ordinary life he has, nonetheless, left a paper trail behind him that we thought worth investigating and writing about.

Alexander Vile

Jacob was the third child of Alexander Vile and his second wife Hannah nee Wiles. Alexander, who was born in 1748 in Smeeth near Ashford. He confusingly married two women named Hannah.

He married Hannah Brown in St. Matthews Church, Friday Street, London. Whether they returned to Alexander’s home town of Ashford or came to live in Deal after they married we don’t know but in 1772 Hannah gave birth in Deal to their first child, a son named Alexander. Three more sons followed but sadly both Hannah and their last child, born in 1777, were not to survive. The baby, William, was born in May and survived his mother by a month.

Alexander very quickly married Hannah Wiles in Hythe in October 1777. The couple went on to have five children one of whom was our Jacob.

Alexander Snr. ran the Crown Inn on Beach Street from at least 1776 when he was listed amongst those who refused to billet Dragoons. He is also listed as a Victualler in the Universal British Directory of 1791.

We found Alexander in the poll book for the year 1790. To vote, at this time, you had to be the owner of property worth at least 40 shillings per year. In Alexander’s case it was, according to the poll book, a house that was being occupied by a C. Abbott.

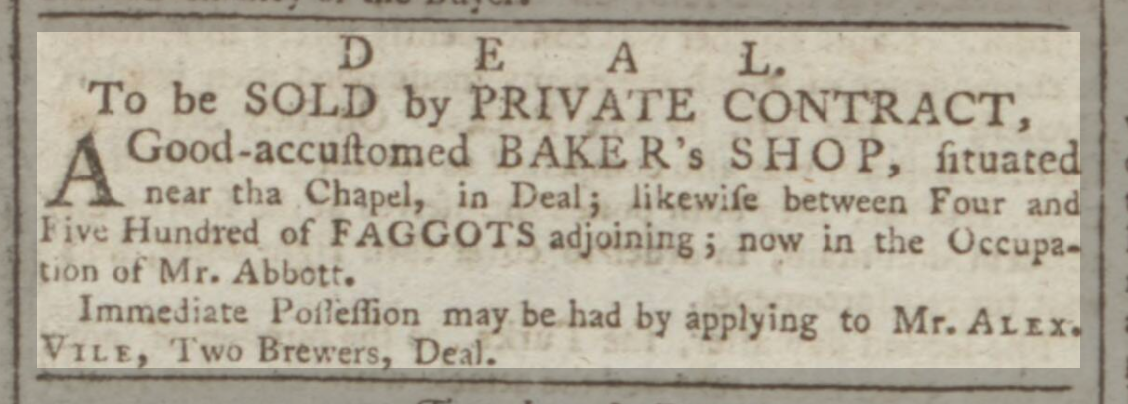

Two years earlier in 1788 an advert was placed in the Kentish Gazette which suggests that ‘Mr Abbott’ was a baker and that Alexander was then running the ‘Two Brewers’ public house, which later became The Paragon, on the corner of Brewer and Middle Street. As Jacob was born in 1784 it may have been here that he was born. Maybe Alexander was a Baker by trade, why else would he have owned a ‘Bakers Shop’?

The four to five hundred ‘faggots’ would have taken up a lot of space. Faggots were basically bundles of twigs tied together. From early times the size of commercially purchased faggots was laid down. Faggots could be made up of any type of wood but had to be 36 inches or 91.5 cm in length and 26 inches or 66cm in width. These were then basically stuffed into the oven, rather like a large pizza oven of today, lit and the door sealed. Once the faggots had burnt away to and the smoke burnt off the ashes were then raked out, the oven mopped around and the bread dough placed into the oven which was again sealed.

The Rates or Cess for the relief of the Parish Poor in 1801 show that both he, and his eldest son, were living or at least paying rates for properties and land in Coppin Street.

In the 1802 poll, Alexander and his eldest son both appeared. As the secret ballot was not introduced until 1872, we know that they both voted for Knatchbull and Geary in this election.

Jacob

As for Jacob himself, in 1798 he was apprenticed to Thomas Vennall, a watchmaker and silversmith in Deal. And by referring to the 1801 Cess we found that Thomas was then living on Beach Street. Whether Jacob lodged with him or remained at home we do not know.

Throughout most of Jacob’s early life France was in turmoil and dealing with revolution. This eventually led to the rise of Napoleon and war with Britain.

Then in 1803 two Acts of Parliament were passed to enable the raising of men for home defence. They have left us with two schedules, known as the Lieutenancy Papers, which list men and their occupations. On these schedules we have found Jacob, his brother, Alexander jnr. and his father.

Both Jacob and his father were not eligible to serve, Jacob as an apprentice and Alexander as he was ‘above age’, he was then 55 years old and his occupation was given as a Housekeeper, meaning that he was a publican, and Alexander jr., was in the Impress Service so was also exempt from serving.

Marriage and Children

Four years later Jacob, having served his apprenticeship, and earning his living as a Watchmaker and Silversmith, married Sophia Gurney Jenkins, who was possibly the illegitimate daughter of Ann Jenkins of Sholden. Sadly she died a year later perhaps having never recovered from the birth and death of her first child. Jacob married for a second time in 1813 to Elizabeth Ralph. They too had a daughter Hannah who was born in 1814. Sadly both she and her mother died two years later at their home in Beach Street. Jacob also lost his father in 1814.

Perhaps it was losing his wives and babies in such a short period of time that prevented Jacob from remarrying for many years. Remarry though he did in 1828, to Sarah Dunn and they went on to have five children and all, except Jacob their youngest, survived infancy.

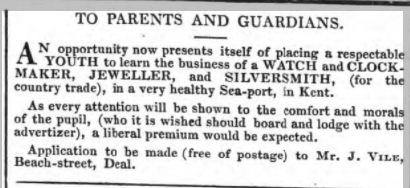

Jacob seems to have continued to live and work on Beach Street as this is where his, and Sarah’s, children were all born and where, in 1833, Jacob advertised for an apprentice. Though who, or if, a young man took up the post we unfortunately don’t know.

Churchwarden

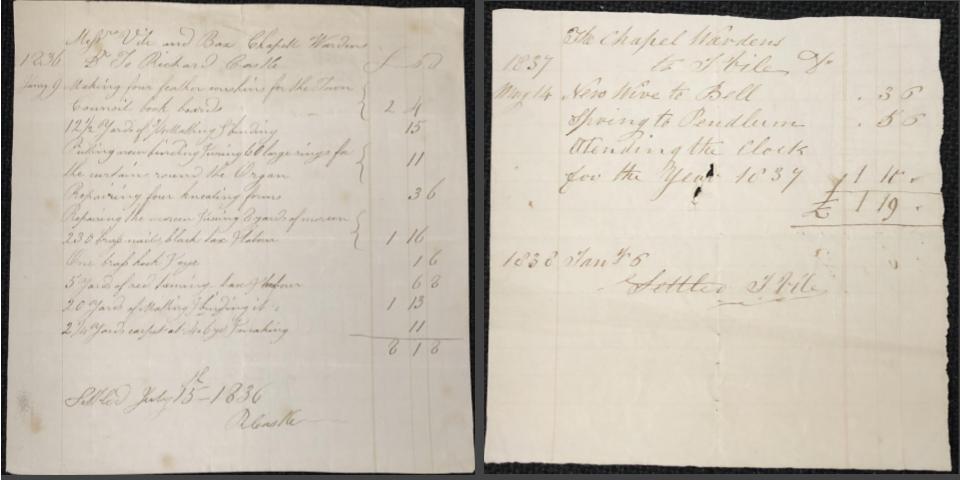

At the beginning we mentioned the receipts from the Churchwardens of St. George’s Church, From these we know that Jacob was a Churchwarden between 1836 and 1838. One receipt was for monies paid, by Jacob and Mr Bax, to Richard Castle for making ‘four feather cushions for the Town Council book boards’. The other was for monies paid to Jacob himself for the repairs and ‘attending of the clock for a year’ for which he received £1 10s 0d.

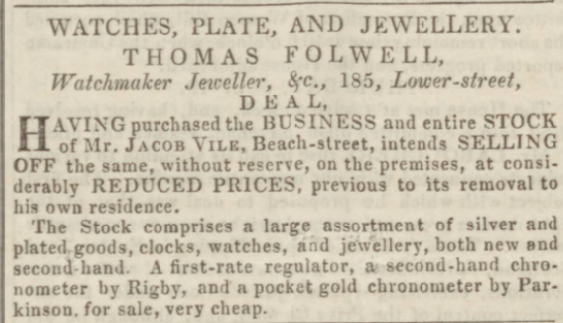

Throughout the 1840s he became occupied with local politics, standing for election as a conservative councillor. Then in 1849 he sold his entire stock to Thomas Folwell. This must be when he became the Proprietor of the Royal Adelaide Baths.

The Loss of a Son at Sea

Jacob and Sarah suffered the loss of their surviving son in 1851. Benjamin had become an Indentured Apprentice in the Merchant Navy in July 1850 when he was fifteen years old. He was onboard the Aberfoil when he accidentally fell from the top of the quarter deck and died. This sad event along with his burial details were published in the Kentish Gazette on May 6, 1851.

Social Clubs

Jacob appeared to be well liked and became involved, not just in local politics, but in local clubs and societies too. He was nominated chairman of the Catch Club in 1838, he was still a member in 1858. The Catch Club was nothing to do with fishing, as you may have expected, but with music. It had its origins in the late 1770s and was a members’ only club with strong political ties which, over the years, became one of the most successful ‘political’ music clubs in Kent. It was dedicated to the enjoyment of, often orchestral music, beer, claret and tobacco.

He was a member of the wonderfully named ‘Duck and Green Peas Club’ which appears to be another social club that involved food and drink and male company. As chairman in 1843 and described as “… Father Jacob Vile…” he toasted the Queen before everyone settled down to an evening of recitation, drinking and singing.

Jacob again appears to have enjoyed himself at the Royal Oak in 1845 when he was amongst many other ‘gentlemen’ of the town who met there on the occasion of the Queen’s birthday. Again much drink and jollity took place.

Final Days

In 1861 Sarah, Jacob’s wife, died, she was buried in St. Andrew’s church on July 4th. Jacob was to outlive her by five years and was buried, not beside Sarah, but in St. George’s Church on 14 October 1866.

In his will he bequeathed a legacy of ten pounds to “…my natural Daughter Sarah Bailey commonly called Sarah Vile…” Nothing else is written about her so frustratingly we can find anything to even suggest who this Sarah was. The rest of the will is turned over to financial matters with his son-in-laws as his executors and trustee; he provided for them and his daughters. With nothing of a personal nature being included in his will for his daughters, who aren’t even named, he basically leaves his estate to his son-in-laws to administer.

A Final Piece of Paper

One final piece of paper that bears Jacobs name is an Indenture for a piece of land that Jacob and Sarah had purchased in 1854 from a Mr. Jelly. We mention this last as it’s a bit confusing as this purchased land seems to be already in Jacob’s possession as indicated on the 1843 Tithe map.

On the back of this indenture is a written reference to the High Court of Justice, Chancery Division, to Jacob Viles’ will and the Trustees Relief Act. The Indenture was used as evidence in the case brought by Jane Woodruff and Edgar Woodruff Thorp of Dover in 1878. Quite why this happened, we don’t know, but it must be to do with either this piece of land and or with the way one of his son-in-laws administered Jacob’s will.